王維:The Wang River Cycle 1-上

Introduction

(words with an *asterix in front are explained in the Glossary at the end. Except that there are no words with an *asterix in front except *asterix; and the Glossary will not be at the end of this article but of Part the Third, with the bonuses and the malices. Words with an *asterix behind them are commented on in a footnote* at the end of the section. There won’t be many, this time. But wait for the glossary! Here’s a preview:

Glossary - index or dictionary in the end of a book explaining only those names and terms occurring in the book that one already knows.

It is my opinion that a glossary serves to show the author’s sense of humor.

And one more thing: Tang is pronounced like ‘t’hung’. In the older Wade-Giles system, previously used to anglicize Chinese, like, up to a decade or two ago, that sound is written T’ang, just like ‘Peking’ would there be spelled Pei-ching. In the modern pinyin method, developed in (Beijing) China, the spelling is Tang. I have decided to follow Wade-Giles. In the spelling of Chinese words I resorted to the following system: either I write in pinyin, in which case I italicize (here underlined): or else I use my own spelling, Sam Taylored,* I hope, to the Merkun pronunciation, ‘in bracketed normal font’.

——————

Footnote:

*If you read this, Sam, 好久不見 - long time no see!

** if you read this, you must be over thirty -five years old with that good an attention span.

——————

Classical music, Sigiswald Kuijken once said, is one of the top achievements in the history of mankind, equal to the Homeric epics, Athenian theater, Gothic cathedrals, Renaissance panting, Shakespeare and the Russian novel (those are my specific examples, but I’m sure his wouldn’t be too different). I agree, and it is an ominous sign for today’s western culture that so few people seem to be aware of that. Chinese landscape painting and T’ang poetry belong on that choice list as well. The spacial depth of the Chinese 山水 Shan-Shui, ‘mountains and rivers’ landscape style is stunning for a style that’s not based on the technique of perspective, developed in the European Renaissance. The mystery of these images is unmatched. Likewise, the imagery of the poetry is condensed and captivating. The Chinese language, like Latin - it may be the only thing the two have in common - has few particles of speech like articles, conjunctions, prepositions, suffixes; and where western words seem to have many seemingly irrelevant syllables, every original Chinese word is a monosyllabic: the syllable is the word. Chinese 義 yì, (say “ee!” in a decisive, slightly annoyed tone) for instance, reflects English ‘righteousness’; another yì, 意, translates ‘significance’, while a third yì, 億 (all in the same, decisive 4th tone), means one hundred million. In English the word impenetrability consists of one syllable to indicate something is not, then the root which has three syllables (pe-ne-tra) that mean nothing by themselves; followed by a fifth syllable to indicate a possibility (denied by the first), a sixth, connecting syllable and finally a last one to indicate ‘noun-ship’. T’ang Chinese may have had several mono-syllabics indicating the same thing, suì, 邃, say “sway”, perhaps being one of them (I’m stretching the truth a bit by comparing a noun with an adjective, but you get the idea). Four or five such words in one line would perhaps equal an English blank verse of 11 syllables. Many Chinese words have multiple grammatical possibilities, like a certain Hungarian word that, I hear, sounds like English “low fuss” and that that according to Finnish linguist Sakk Laamahängen (PhD) appears in colloquial as noun, adjective, adverb, interjection, conjunction, preposition and other grammatical functions, while it however has yet to be listed in a dictionary.

The first line of the famous poem 鹿柴, Deer Camp, the fifth of Wang’s collection, may suffice:

(I don’t know about computers, but I understand that you need a landscape view in order for this blog post and most others of mine to work)

空山,不見人

empty mountain, not see man (5 syllables),

h a s b e e n t r a n s l a t e d :

Too lone seem the hills; there is no one in sight there (12 syllables, JB Fletcher (sic!) 1919)

There seems to be no one on the empty mountain (12, Bynner/Kiang 1929)

No glimpse of man in this lonely mountain (10, Chang/Walmsley 1958, as third line!)

On the lonely mountain I meet no one (10, Chen/Bullock 1960, on two lines)

Deep in the mountain wilderness where nobody ever comes (15, Rexroth 1970, the poem counting 7 lines!).

Empty hills, no one in sight (7, Dr. Watson, 1971, who I hear was tone-deaf)

Empty mountain; no man is seen (Yip and Yanneke 1972)

No se ve gente en este monte (10, Octavio Paz, 1974)

Montagne déserte. Personne n’est en vue (9 or 10, Fr. Cheng, 1977)

Not the shadow on (sic!) a man on a deserted hill (13, Chang 1977)

Capitol Hill: humans, no longer there (10, Trump/Pence 1984)

De lege berg: je ziet geen mensen (9, Idema 1991)

In the Chinese, almost every syllable is an image. No articles like the which according to David Breitman the Dutch don’t know how to spell; no prepositions like in, at or on account of; the 8 or 9 syllable line yeah, but I’m about to take it out could be expressed in T’ang Chinese in three or four. In most cases, personal pronouns are also left out: the reader must decide if the poet himself sees no people, or if an unspecified viewer is not capable of that perception. The line has only one regulator: 不, ’pooh’, not. The Tao of Pooh …

(again, when I give the English trans-lit-e-ra-tion (翻) in italics (here underlined) it is in pinyin, the made-in-China system currently used all over the world, which can be recognized by its Qs, Xs and Zh as beginning letters, and which no one knows how to pronounce, though the rudiments of it only take about 20 minutes to learn. When on the other hand I give it in straight font in ‘quo-ta-tion-marks’ (引號) it’s my own attempt to make it sound most like American English. Thus, 邃 = suì in the pinyin system, my own spelling would be ‘sway’ - after having it checked by my beloved editor Marie-Thérèse = 瑪麗·特蕾絲). For more information about the different transliteralizifications see ==> my article Lingerie in this blog. This may be funny, but it is not a joke.

——————

T’ang poetry is strongly shaped by the Taoist spiritual ‘Platonic’ view of emptiness: what can be defined is not what’s real. This view has also strongly influenced Buddhism, resulting in the extremely quietist, meditative and effective Chan, Ch’an form of Buddhism, which in Japan of course became Zen. The problem with these thought systems is that any attempt to formulate or define them is futile: the way that can be walked is not the way. David Hinton in his little book the Selected Poems of Wang Wei writes about it in quite eloquent terms for about 10 pages, but my right brain is too underdeveloped to really grasp what he is saying if it is anything other than what I just said here. Also, I’m not a Taoist/Buddhist, I’m a Christian. I can only tell what this poetry does to me, European Gringo (鬼佬). To me, Wang Wei’s landscapes - he was also a nationally celebrated landscape painter, though no direct works of his seem to have survived - evoke stirrings from what C.G. Jung calls the collective subconscious, images of a primeval past, similar to the remnants of the phenomenally gorgeous Minoan civilization or naturalist drawings of a Jurassic or even earlier, a Devonian forest. Dinton calls it the inner experience of landscape, of which he claims Wang Wei is the first champion. He sure lived before Ruysdael or Ruisdael (same name, different guys, both known for their landscapes). But wouldn’t landscapes as genre appeal to equivalent mystic experiences in all art forms over the globe? Aren’t we equally drawn to the shadows in Jan Brueghel’s Forest landscape with Deer Hunt as to the mists and mysteries in Don Juan (董源, Dong Yuan d.962)’s Dong Tian Mountain Hall 洞天山堂? (for images see the Carousel at the end). To what extent can art theory actually ruin our experience?

Wang Wei’s Wheel Rim (Wang) River Collection 輞川集 consists of 20 poems of 4 x 5 = 20 syllables each (if the math is too hard for you, do not read my article about intonation). This was a popular verse form, somewhat comparable to our western 4343 lines, perhaps, as in uns ist in alten maeren … wunders vil geseit // von Helden lobebaeren … von großer arebeit, the rhythm of the Nibelungen song: from ancient recollections, we hear many a tale // great deeds, brave heroes’ actions, and their renowned travail …- or perhaps the Roses are Red collection, as in Roses are red, that much is true, but violets are purple, not f@#$ing blue. A simple pace, in which the images are pure, with ample time and room for reflection. To get an idea of the potential of this genre, behold three of my favorite poems so far, not by Wang Wei but, as an opening act, by others surrounding him. The poems are given in traditional form from top to bottom, then from right to left, with traditional, not simplified characters, as still used in Taiwan, Singapore and China Town, and perhaps Hong Kong, but not in mainland China. Just like Kissinger once assured Israeli prime minister Golda Meir that she needed to realize he is first and foremost Secretary of State of the US government, then a US citizen, and only in the third place a Jew. Yes, Meir answered, but in Hebrew we write from right to left… In mainland China they now write like English from left to right. I think that’s where they drive their cars also. I know I could make some comedy by turning a corner (humor is always about turning a corner) to the political meaning of these adjectives, but I’ll let that go for now.

The first one is by 賈島 Jia Dao (early 800s): Visiting a recluse and not finding him home.

尋 ⬅

雲 只 言 松 隱 ⬇

深 在 師 下 者

不 此 採 問 不

賈 知 山 藥 童 遇

島 處 中 去 子

Search recluse (person) not meet / pine under ask boy (person) / says master pick herbs go / only in/at this mountain midst / cloud deep not know where

Visiting a recluse and not finding him home

Under the pine I ask the boy

Says Master’s out picking herbs

He’s there on the mountain - dense

the cloud - he can be anywhere

(tr. 渡復興 Ferry Reno)

——————

First of all, I relish the typical Taoist notion, almost a genre, and much older than the T’ang dynasty, of going up a mountain to visit a master and not finding him in. It’s not only somewhat hilarious for us westerners, on a deeper level it carries all colors of the human spectrum, from mysterious, to lonely, to man alone in nature, the vanity of effort, and, as the Buddhist said to the hot dog vendor, make me one with everything. As T’ang titles go, this is a relatively short one: Li Bai has a poem called Going to visit the Daoist master on Daitian mountain but not finding him; Wang Wei even has a “In Reply to Official Sue from Yu District who Came to my Villa in the Blue Lands and I was Not There to See him and Welcome Him as a Proper Host Should”. Darwin has On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle of Life. Dinton tells me that the mountains around Wang Wei’s summer villa - about that in a minute - reach to 3,000 meters. I would expect him to exaggerate - he seems that kind of guy - but the highest mountain of these Qinling mountains, Taibaishan 太白山, only 60 miles from the T’ang capital Ch’ang An (today’s Xi’An), is 3, 676 m., that is 12,359 feet or 148,308 inches, or 2,282 times a man the size of Napoleon and 2,557 times the height of Mime Yamahiro Brinkmann (山広美芽, ‘shun-kwung may-ya’).

Then there is the parallelism.

This poem doesn’t have parallelism.

Instead, the outlook of the poem, the scope goes from clear to unclear, the certain to the improbable, from knowledge to ignorance, from comfortably sizable to cosmically huge, from daily life to spiritual contemplation: under a solid pine tree (symbol of primeval universality) I ask the solid, “real life” boy, who begins the wrapping in mystery: the master is not here (absent, hearsay), he is there on yonder mountain (space, distance, cosmic dimensions), the cloud makes him ‘vanished’, ‘lost’ (impenetrable, inaccessible spiritual dimension, the world of appearance, reality will always be beyond our grasp.). The cloud evokes the clouds of the Chinese landscape paintings, which as artistic technique create depth perception and give this deep sense of mystery, geographically, emotionally (the depths of the soul), existentially (the hidden meaning of life). This poem is a summary of the art of meditation, to completely disentangle oneself from the dumb little worries of daily life and be transported to the dimension of the more real world of universal meaning, purpose, call. These are but words; I hope you get my drift, or rather, and much, much better, the drift of the master in the poem.

In the West we have the Socratic idea of ignorance: the more you know, the more you know you don’t know anything. What can be known is not knowledge. The way that can be traveled is not the way.

Another favorite of mine is a poem by 柳宗元 Liŭ Zhōngyuán (773-819), River Snow, which is almost a direct translation of a landscape panting into words.

江

獨 孤 萬 千 雪

釣 舟 徑 山

寒 簑 人 鳥

柳 江 笠 蹤 飛

宗 雪 翁 滅 絕

元

River snow / 1,000 mountain bird fly end / 10,000 path man footprint vanish / lonely barge raincoat broad-rimmed-hat vanish / alone fishing cold river snow / Liu Zhongyuan)

River Snow

A thousand hills, all birds have flown away

Ten thousand trails, man’s footprints all but vanished

Lost barge, old man, raincoat, brimmed hat

Fishing alone in the freezing river snow …

(tr. Ferry Reno)

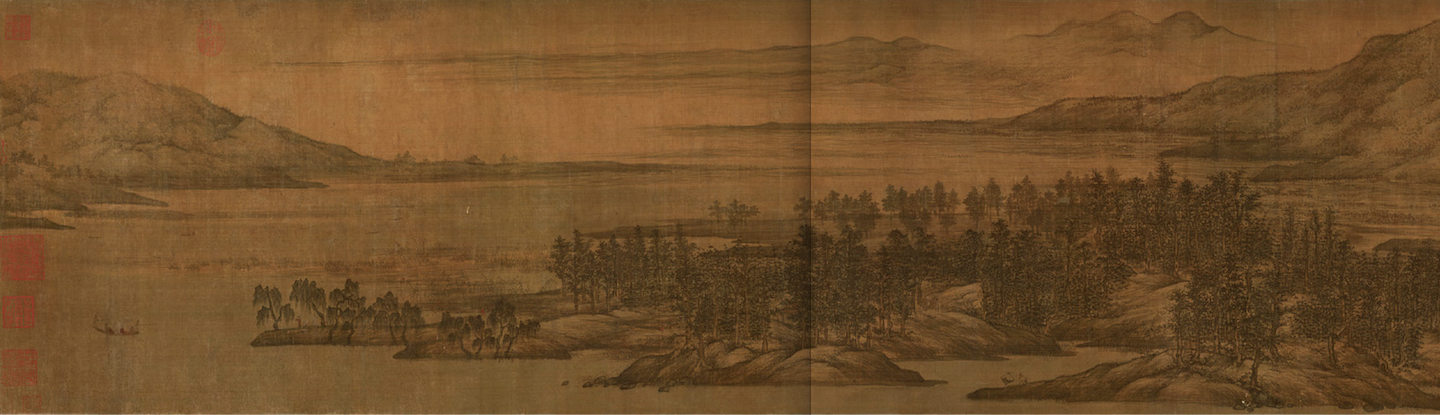

Here we go from the universal to the particular. The setting is monumental: thousands of hills following each other in a waving rhythm of rounds, somewhat like the landscapes by the 10th century painter whom I call Don Juan (董源, Dong Yuan, d.962) and whom we have already seen above. Ten Thousand trails - Chinese actually has a word for 10,000 as well is 10 million, as we have already seen as well - and an overwhelming emptiness have taken hold of our imagined trip: birds have flown away, footprints have vanished, or never were. Then minuscule, infinitesimal, minute, all those great words in English stressing smallness by their spelling and pronunciation idiosyncrasies, a lonely skiff, with an old man described in vivid terms, one with nature, enduring the cold - the Chinese has snow as the last word …

Here is an example of how literary theory can obstruct our enjoyment of poetry. I read over and over again about man’s hardship, his insignificance in his surroundings, the gloomy lives - and that is undoubtedly all true, but that is not at all what I read in these poems, or why I read them. It is a little bit like Godfried Bomans’ article about Scotland Yard’s 100the anniversary or something, in which the superior intelligence of their agents is praised for “having contributed to the fame of the organization” (I paraphrase). Bomans writes that the agents of Scotland Yard are undoubtedly of great intelligence, but that is not what made the institution famous: that was done by the idea that they are all idiots who cannot solve the crime and then beg the Great Detective for help. Hardship of life, sure. But had I felt any of those things, or had I felt those things alone, I would close the book and never read that poet again. The small size of man, to me, signifies the enormity of nature, of God’s creation, therefore of our existence, of the infinity of the mystery surrounding us, that infinite spiritual force from which we can tap and on which we can feed at any moment of our lives. Archie Barnes, whom I wish I had known, stresses the hardship the man has to endure: Wang Wei, he says, loves to write about kitchen smoke emanating from the chimneys of village huts, about voices across the pond, barking dogs, crying crows, the warmth of social simple life: while here we have the flip side of the so popular solitude propagated in T’ang poetry. Still, that’s not why I read this poem. Couldn’t the man in the raincoat with the broad brimmed hat be so ‘one with everything’ that even winter cold cannot bother him any more? Couldn’t this be a monk who has stripped his life from every unnecessary luxury and has learned to live the pure human life? For sure Wang Wei’s (here Liu Zhongyuan’s) poetry sings the mysterious beauty of nature, which I think of as lingering on an infinitely higher level than particular human emotions which we find in a Verdi opera or, more repressed, in most Hallmark movies. I’m thinking of a passage in the Iliad I read in school (!!!) where a smoldering fire is described, how it is covered with mull sand so it can still breathe, thus kept for three days, then rekindled by the farmer for further use. Microscopic I believe might be the word that comes to mind when we compare Kim Kardashian to that. All right, the last line was not very helpful. I apologize.

周文靖, Zhou Wénjìng - 山水圖, Landscape with River Snow.

We (that is, the Chinese, so not president Trump) actually have a landscape painting with a line from this poem inscribed on it. The T’ang people used to have a different idea of original art than we do: they thought that those personal stamps in red ink you find on every panting, or personal poetry lines added by the owner, belong to the art work, which thus acquires a collective dimension of belonging to the community. The painting is by 周文靖, Zhou Wénjìng - 山水圖, Landscape with River Snow. The lines on the top right corner are 孤舟簑笠翁,獨釣寒江雪, lonely skiff, man, broad hat, raincoat // angling alone in the cold river snow.

Tell me honestly, do you see wretchedness or serene one-with-everything-ness in the painting? Do you see a nasty, mean and hard nature or a magnificent one of unspeakable beauty? This was Zhou’s view from around 1463. Note how little landscape painting had changed in the 500 years that had lapsed since Don Juan. But about reflective surfaces and the Roman Catholic Church another time.

Finally, and this time for real, the parallelism. Between line 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 (the spaces between 1 and ‘and’ and ‘and’ and 2 and 2 and ‘and’ and ‘and’ and 3 and 3 and ‘and’ and ‘and’ and 4 are supposed to be equal) - I mean between each even line and the odd line preceding, the words reflect each other. In the first two lines 1,000 reflects 10,000; mountains reflects path; we have bird & man, fly & footprints, finally two words 滅 (‘tyuè?’) and 絕 (‘me-yeah!’) that express disappearance and ending. In the last half lone & lonely, boat & fishing rod, raincoat & cold; the last three words of line 3 and 4 match structurally, with the last geezer and snow being qualified by the two preceding ‘adjectives’. Archie B. goes as far as seeing connection between the snow and the old man’s snowy hair …

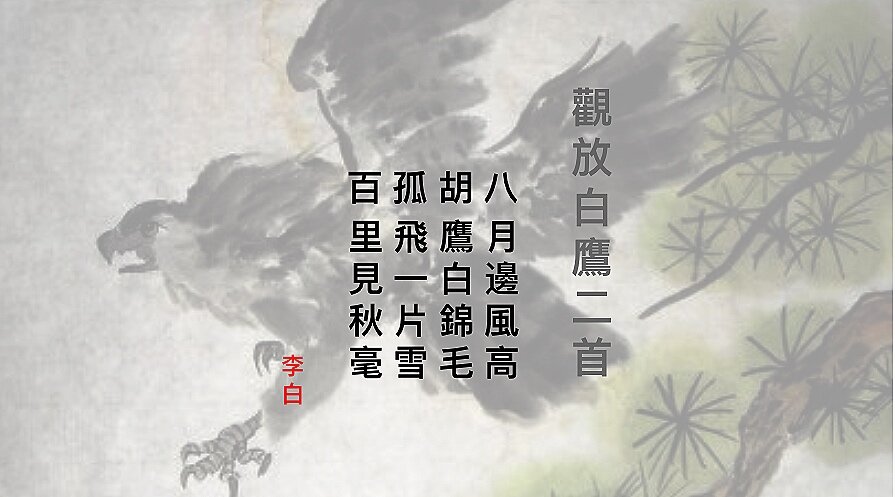

Now we have to read on until the painting on the right is “past” to show the next poem, because it needs its own space. That one is actually by arguably the greatest or the second greatest of all Chinese poets, 李白, Li Bai (‘Lee Pie’ as in the Hungarian aide-de-camp at a Confederate conference asking the chef if the dessert he finds in the kitchen is the Stonewall Jackson pie or the General Lee pie?). this is the ‘Li Tai Po’ of Mahler’s Lied von der Erde. Li Bai apparently was a magnetic personality, giving rise to nicknames like "Immortal Exiled from Heaven", a name given to him by fellow Taoist poet 賀知章 He Zhizhang. When I read Li Bai I think of Beethoven (路德維希·範·貝多芬, sorry, couldn’t resist), his poems have a heroic, boisterous, individual, Michelangelic, Dühreresque, Schillerian (not Kardashian) idiom. I see Frans Hals rather than Johannes Vermeer, Michelangelo rather than Rafael, Handel rather than Bach, Corneille rather than Racine, Victor Hugo rather than Proust, Peter Ustinov rather than Paul Suchet, Orson Welles rather than David Niven, LeBron rather than Stephen Curry. Li Bai, the drunk poet, the drifter, known for his continuous travel. I think we have past the Zhou Wenjing painting now and can proceed to the poem, the White Falcon let loose. This is not a description of a running back scoring a touchdown on a kick-off return for a southern NFL team in a road game …

Watch let go white falcon (II) / 8 month side wind high /barbarian falcon white brocade feather / lone fly one flake snow /100 li see autumn speck (one hair)

Watching a white falcon set loose

High in September’s frontier winds, white

Brocade feathers, the Mongol falcon flies

alone, a flake of snow, a hundred miles

Some fleeting speck of autumn in its eyes

(David Hinton)

I think this expresses the individual’s loneliness, the drive to independence and to look for essentials, and the separation that comes with that quest, because most people do not seem to be interested in that most of the time (I still hope everyone wants it some of the time). Archie, from whose book I got many of these poems (though not this one), gives a verse (p.117) by Zhang Jiŭling 張九齡 (678 - 740) about a goose that flies beyond the reach of the hunters. “But now I’m wandering too high too be seen clearly, so how can de fowler be after me?” I love the image more than the poem it came from, which I will give in the appendix, to show how too much specification hurts great poetry.

I am not sure about the translation of the last line in the Li Bai poem. My impression of Dinton is that he sometimes goes for effect rather than truth, but who am I to judge these highly qualified specialists? In beauty, his language far surpasses most other translators, who seem more ‘academic’. I also like his wild hair and piercing eyes (see Carousel). I love the image of the poem, the free falcon, lone ranger, far from the snares of society with its politics and its hideous monster of political correctness - the same rare feeling I had on top of a high mountain like Humphrey’s Peak in Arizona. Freedom, though in the most profound sense. Here it shows in the astronomical height of 100 li (± 30 miles) the bird flies above the world; the image of such high, independent and lone flying and the energy and freedom implied - Chinese doesn’t really seem to have a word for free - I do not expect to find in the quietist, adapting Wang Wei. Just like Bach, Wang never attempts to physically break out of the confinements of the world; instead he seeks liberation in prayer and spiritual contemplation; Li Bai and Beethoven seem to idealize freedom in action, with every breath they take. Two opposite ways of acting out one’s individual Dasein.

But perhaps Wang Wei’s angler and Li Bai’s falcon are one and the same soul: leaving the world of the department stores and finding meaning in one’s bare existence, in proximity to the elements from which we are created …

——————

T’ang Chinese

T’ang Chinese differs in two major ways from Mandarin. First, it sounded entirely different. Chaucer’s Middle English of 650 years ago is already unintelligible for an uneducated bulldog or Philadelphia eagle, and that is still written in a phonetic script: Chinese indicates meaning, not sound*. Wang Wei lived before Charlemagne of whom we don’t even know what language he spoke. How different T’ang Chinese sounded I show in a moment according to another poem by Li Bai. The change in pronunciation since T’ang times, for whatever reason, evened out the sounds until Mandarin has a system of about 150 sounds, which, multiplied by the four tones, yields 600 unique sounds for about 6000 monosyllables found in a big Chinese dictionary. That’s way too many homonyms. In modern Chinese therefore, almost every word is reinforced by another word, like in true Hegelian dialectic: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. 師 shī (‘shih’) meant ‘teacher’, ‘master’. My Ricci Institute Chinese-French dictionary shows about 70 different characters, which means 70 different words for this sound, and even though relatively few use the first (high) tone (only 11), Mandarin needs a clarification: 教師 (‘chow shih’), 教 being a word for ‘teach’. Most Mandarin words have two syllables in that way, where each of the syllables originally had its own meaning. But in T’ang Chinese, most words were still monosyllabic, because there were probably fewer of them, and also because they were more distinct from each other. Isn’t it fascinating that we could not come up with a monosyllabic word for monosyllabic? Similarly, palindrome is not a palindrome and onomatopoeia not an onomatopoeia. I’m digressing. A glimpse of our reconstructed T’ang pronunciation you can see here in another poem by Li Bai, of which I give both T’ang and Mandarin pronunciations. I don’t really know how this reconstructed T’ang spelling sounds: when linguists begin to talk about fricatives, affricates and and frontal spirants, they lose me. I also wonder when you dissect a poem until all functions of each word are accounted for, do you still have a poem left?

Who kills a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom (‘Gandalf’).

Night yearning

夜思 - Yè sī

Hanzi Mandarin T’ang

➡ 床前明月光 chuáng qián míng yùe guāng jrhiang dzjen miang nguaet guang

疑是地上霜 yí shì dì shàng shuāng ngi dzĭ dhì zhiàng shriang

舉頭望明月 jŭ tóu wàng míng yuè giŭ dhou miàng miaeng ngiuaet

低頭思故鄉 dī tóu sī gù xiāng dei dhou si gò xiang

李白 Lĭ Bái Lĭ Bhaek

Waiting at Night Night yearning

On my bed moonlight? Before my bed the bright moon shines

or frost fallen? I It’s like there’s hoarfrost on the floor

look up to the bright moon Lifting my head I’m watching the bright moon

look down to my old home Lowering my head I think of the old country

(Bill Keith) (Ferry Reno)

This is one of the most famous poems in Chinese literature. The last two lines I found in several language teaching methods for beginners. The moon was associated with exile, because it could be shared by people living thousands of miles away. Thus it triggered memories of, and frustrated yearnings for, closeness. The hoarfrost on the floor immediately adds mystery, dudn’t it? Comparing the T’ang with the Mandarin pronunciation, here given in pinyin, the first thing we find is Li Bai’s name: which in English, as we saw, might spell ‘Lee Pie’ with a Hungarian, French or Dutch, but not German or English [p]; However, in ‘T’anguese’ it should sound like P’hack pr Pack, I think that’s the vowel they indicate with ae. Also moon, 月, ‘yüèh’ (in pinyin the accents indicate tones, but here I mean the [e] in ‘red’ or wèèèh), must have sounded really different, nyüat or nyüèt or something. In Mandarin, the explosives like [t] and [p] that still exist in related East Asian languages like Cantonese (Sun Yat Sen, 孫逸仙, which in Mandarin sounds like ‘Soon Ee Seeyèn’), have completely disappeared from the endings of words. Incidentally, in this case, the rhymes still work in Mandarin, up to the tones; in other poems you will not find that the case any more.

The way we pronounce these poems today in Mandarin sounds nothing like how they sounded in the 8th century. That, for a musician, is a disappointment we have to accept. The way it sounds is not the way it was meant to sound. Pronouncing T’ang poetry in Mandarin is like Bach’s suites played by Casals or Van Gogh pronounced ‘Van Go’: generally accepted, but sounds nothing like Bach imagined it or Vincent pronounced it (for more about the autonomy of language however see ==> Lingerie).

——————

Footnote:

* Sometimes I am told that most Chinese characters have sound elements, but those are never absolute. The character 清 , ‘ch’ing’, = ‘clear’, has 氵(water) as radical and 青 (‘ching’ = blue, green) as sound element: but that only means “sounds like green”, like in a game of charades. 青 in Japanese means ‘blue’ and is pronounced ‘ao’. Chinese sound factors are only relative, like Minoan pot A can only be dated in relative terms: it is ‘from the same time as Minoan pot B’. How Chinese ‘green’ could become Japanese ‘blue’ is easy to clarify: 青 stood for a whole assortment of different radiating colors, mostly from nature, with blue and green at the center. A shiny black could be 青, as I understand it; while the ubiquitous moldy green in the kitchen and bathroom of an apartment when I am the one responsibly for cleaning would have a different word —— Homer’s wine-dark sea’ shows that exact color perception, that is, awareness, has come late in history: Homeric people did not seem to have a word for blue. Other words of the 青 series are 情 (‘ch’ing?) = ‘emotion’, with the ‘heart’ radical, 請 (‘ch’ing…’) = ‘please’, with the radical ‘speak’; 晴 (‘ch’ing?) = ‘clear’ with the radical for ‘sun’; 鯖 (which the pinyin input method lists as ch’ing but Google Tranny gives as “chung” as in ‘dung’) with radical ‘fish’ = mackerel: 精 (‘ching!!!’) with the ‘rice’ radical = fine, seminal, perfect; 睛 with radical ‘eye’ = ‘eye’; 猜 (‘ts-hi?’) with the ‘dog’ rad = ‘guess, suspect, speculate’.

——————

My own amateur attempts

Given the 5-syllable nature of the 五言絕句 wu yán jué ju, I have attempted to bring that form over in Chinese and write my own recreation of the Wheel Rim River 4-liners. Something got to give: in English, 4 x 5 (or 6) syllables is not enough to capture everything that is in the much more concise Chinese: but a mood can be created, and the Chinese rhymes will at least be approached. I also found it a good exercise for conciseness. As example I will give two such attempts, wu yán style, about European historical events.

480 BC 1809

O stranger, please announce Napoleon at his grave

to folks back home, still praying gave his salute, a bow

we rest under these mounds - “If he were still alive

the oaths we swore obeying I wouldn’t stand here now”

The one on the left is in reference to the 300 Spartans who died at the Thermopylaean Pass in 480 BC, which Simonides of Ceos (556 - 469 BC), according to Herodotus, immortalized in the unforgettable distich ὦ ξεῖν', ἀγγέλλειν Λακεδαιμονίοις ὅτι τῇδε // κείμεθα τοῖς κείνων ῥήμασι πειθόμενοι" (Ō xein', angèllein Luck a die moan knee yóyce hotty tey-de // keimetha toyce keinoan rhèmazi peithomenoi) = ‘Go, tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, that here, obedient to their laws, we lie.’ - (I thought that rhèmata are words, therefore oaths)

In the 1809 poem, HE is Frederick the Great, who had died in 1786, the year of Le Nozze di Figaro.

It goes without saying that these attempts of mine are little help for acquiring a better understanding of Wang Wei’s poetry, as they are re-creations, not translations. I just include them because, well, it’s my blog and I can post here whatever I want.

Don Juan 董源, Landscape with Ferry (10th century)

—————-

The Wang River Estate

The Wang River Estate (輞川谷 = Wang Chuan Valley), Wang Wei (王維) probably purchased in the middle of his life. We do not know how many times he retreated there and which poems except obviously the Wang Chuan Ji, he wrote there. The twenty poems were provided with an answer by Wang’s friend 裴迪 Pei di (‘pie tea’), with, like Monty Python’s public accountant, ‘doesn’t seem to be of the slightest consequence’. From what I gather, Imperial China had a culture-oriented but humanly rigorous system in which men were pawns and women counted for even less; neo-confucian ideology, which, as Taoism’s corpse, has permeated Chinese society ever since the common era, reduced the value of a human being to how he or she fulfilled the social obligations attached to his or her position as first, second or third son or daughter in the family and whatever function he or she held in the state or home hierarchy. Most prominent in the life of a functionary, who entered the ladder of society with the brutally hard and mindlessly monotonous state exams in which knowledge of the classics was tested, was the inner strive between the individual’s obligations and his inner needs. Many poems for instance mention the 1000 li distance between an envoy sent to the frontier and his wife who remained in their house. The alternative to this hierarchic treadmill was withdrawal in lone contemplative meditation. Wang’s Wheel Rim River cycle shows the place where such a retirement could take place.

The names of the translators I have changed, to add some fun, no disrespect intended. Also in my criticisms I call them as I sees them, and I’m aware that a dumb statement like some critic’s classification of Beethoven’s Violin concerto as “lacking unity”, makes the critic, not the artist, immortally ridiculous. The real names of the published translators (the unpublished ones I tend to leave in peace) will be found in or after the glossary at the end.

——————

WANG WEI’s INTRODUCTION

in Japanese: ‘inü-tüdo-dükü-shan’.

余別業在輞川谷。其遊止有孟城坳,華子岡, 文杏館,斤竹嶺,鹿柴,木蘭柴, 茱萸沜, 宮槐陌, 臨湖亭, 南垞, 欹湖,

柳浪,欒家瀨, 金屑泉, 白石灘, 北垞, 竹里館, 辛夷塢, 漆園, 椒園等。與裴迪閒暇。各賦絕可云爾。

“My retreat is in the Wang River mountain valley. The places to walk include: Meng Wall Cove, Huazi Hill, Grained Apricot Lodge,

Clear bamboo Range, Deer Enclosure, Magnolia Enclosure, Dogwood Bank, Sophora Path, Lakeside Pavilion, Southern Hillock,

Lake Yi, Willow Waves, Luan Family Shallows, *Gold Powder Spring, *White *Rock Rapids, Northern Hillock,

Bamboo Lodge, Magnolia Bank, Lacquer Tree *Garden, and Pepper Tree Garden.

When Pei Di and *I were at leisure, we each composed the following quatrains…”

(tr. Polly)

——————

1. MENG CHENG HOLLOW

空 來 古 新 孟

悲 者 木 家 城

昔 復 餘 孟 坳

人 為 衰 城

有 誰 柳 口

Meng Cheng cavity - new home Meng Cheng mouth / old tree remnant wither willow / come the-one again because who? / vain grief former man have

Meng Cheng Cove Mêng Ch’êng Valley

A new home at the mouth of Meng Wall: My new home stands sentinel at the entrance to Mêng Ch’êng

Ancient trees, the last withered willows. Where, of an ancient wood, only time-worn willows still remain ...

The one who comes again - who will it be? Who would want to come live in this lonely place

Grieving in vain for former men’s possessions. (Polly) Unless to brood over the sorrows of the past? (Chang/Walsmley)

Chang/Walmsley (Chang probably Zhang in pinyin) add some words, ‘sentinel’, and 木 (‘mooh!’) is translated as a once existing forest (which makes little sense, when the previous owner grows too decrepit for maintenance, a forest should emerge rather than disappear); my problem is with the intention of the last two lines: shifting the focus to the gloominess of the place (inconsistent with the rest of the series) instead of the eternal cycle of life-death and the passing-on of possessions.

Meng Wall Hollow Meng Cheng Valley

I made my new home at Meng Wall My new retreat is by the walls of Meng,

Old Trees? Only some rotting willows By withered willows, knarled (sic) and ancient trees.

After me, who else will lodge here, Whoever comes here later will pity in vain

aimlessly grieving for past owners? (the Barnstones) My years that pass with neighbours such as these (Chaos)

The Barnstones (I believe Fred and Wilma, but I may be wrong, see *bibliography) specify the first person as the narrator. That is possible (who am I to criticize?) but it does limit the cosmic infinity of the imagery. Same with the question mark after ‘old trees’. —— As for the Chaos: “We three kings of Orient are - We English not speak very well ….”. Always problem in cases target language not first language. I wonder who neighbors supposed to be. Torontonians my experience always very polite.

Elder Cliff Cove New home on the river

At the mouth of Elder Cliff, a rebuilt house new home on the river

among old trees, broken remnants of willow. some spent willow wood -

Those to come: who will they be, their grief the one before me - shiver -

over someone’s long-ago life here empty. (Dinton) he? she? - gone, for good. (Ferry Reno)

“Wang Wei’s house here had previously belonged to the distinguished poet Song Zhiwen (‘Soong Chih-wun’) who died in *712, and to whom (this) poem may be taken to allude - as well as to Wang Wei himself.” (Commentary by Mrs Robinson, whose translation for this poem didn’t make it in this anthology. It didn’t have the right documents)

——————

2. HUAZI HILL

惆 上 連 飛 華

悵 下 山 鳥 子

情 華 復 去 岡

何 子 秋 不

極 岡 色 窮

Blossom (-) ridge / fly bird go no limit / continuous mountain again autumn color / up under Blossom (-) ridge / regret desolation feel what extreme

Huazi Hill Master Flourish Ridge

Flying birds leave endlessly. Birds in flight go on leaving and leaving.

On continuous mountains autumn colors return. And autumn colors mountain distances again:

Up and down Huazi Hill: Crossing Master Flourish Ridge and beyond,

Melancholy - what limits to these feelings? (Polly) Is there no limit to all this grief and sorrow? (Dinton)

Huatzu Hill Mount Hua-tzŭ

Flying birds away into endless spaces Birds sail endlessly across the sky.

Ranged hills all autumn colors again Again the mountain range wears autumn’s hue.

I go up Huatzu Hill and come down - As I wander up and down Mount Hua-tzu

Will my sadness never come to its end? (Mrs. Robinson) Deep shafts of sorrow pierce me! (Chang/Walmsley)

Huazi Hill Blossom Hill

Migrating birds are leaving endlessly, birds fly, disappear

fall colors come to mountain after mountain. rich reds on endless hills

All the way up Huazi hill a sadness lone rhythm, quite end-of-year

staining every far boundary, drifts on. (the Barnstones) a sense of loss instills (Ferry Reno)

The last line in the Chinese shows a great alliteration at least in Mandarin: ch’ho ch’hung ch’hing, which also suggests deep sighing. Supporting that, the three characters 惆,悵,情 each start with the (short) root for heart 忄, underscoring the alliteration. —-- I wonder if Dinton (David Hinton, see bibliography)’s translation of Master Blossom comes from Hua-tzu, 華子, of which the suffix tzu, 子, reminds of the great masters 孔子 K’ung tse (Confucius), 孟子Meng’tse; even though the last character, that originally means child, serves as a modifier for many ‘ineminent’ objects, as in 裙子 ‘ch’hüntze’, skirt.

——————

3. GRAINED APRICOT LODGE

文

去 不 香 文 杏

作 知 茅 杏 館

人 棟 結 裁

間 裏 為 為

雨 雲 宇 梁

pattern apricot lodge / pattern apricot cut cause beam / fragrant grass tie cause roof / not know main beam in/*at/there cloud / go make *man space rain

Grained Apricot Lodge My Study among Beautiful Apricot Trees

Grained Apricot cut for beams; Slender apricot trees pillar my hermitage,

Fragrant reeds woven for a roof. Fragrant grasses thatch it;

I do not know if clouds within the rafters Mountain clouds drift through it -

Go to make rain among men. (Polly) Clouds, could you not better make rain for needy peasants? (Woolmsley)

Grainy Apricot Wood Cottage Apricot-Grain Cottage

Its beams are cut from apricot wood, Roofbeams cut from de deep-grained apricot,

its roof is woven of fragrant reeds. fragrant reeds braided into thatched eaves:

I wonder if clouds under the rafters no one knows clouds beneath these rafters

float into the human world as rain. (Barnstones) drifting off to bring that human realm rain. (Dinton)

Apricot Wood House Grained apricot lodge

Straight-grained apricot to make the beams grained apri’ cut for beams

Fragrant reeds woven to make the roof bound reeds, a fragrant roof

Perhaps clouds do form in these rafters thin clouds form micro streams

And go and make rain among men. (Mrs. Robinson) under the eaves, aloof (Ferryman)

Polly writes: “The last two lines allude to the second of Guo Pu’s (276-324) “Seven Poems on Traveling with Immortals (You xian shi qi shou, Anthology of Immortals, 21/292/5) which reads: ‘Clouds arise within the rafters / Winds emerge from the windows and doors.’ This is a description of a Taoist priest, to whom Wang Wei is thus suggesting a comparison.” Mrs. Robinson says: ““The notion of the clouds forming in the rafters is taken from a 4th century Poem of the Traveling Immortals, and so this is fancied to belong to the immortals.” I find that image of the clouds under the rafters totally cool, like the micro climate that they say sometimes occurs in airplane hangars. Also, don’t you see a typical Chinese pagoda? —— For the rest, I like Chang/Walmley’s translation; being from the beginning of the last century, it is quite free and often not original at all, but it somehow seem to enrich my understanding of the poetry.

I like the immobility of the first half

Finally, in my own attempt, I’m not sure if apri-cut is a permissible use of the English language. In Dutch it would work like woodwork, as Cesar Gezelle sings: k’zie schapen witgewold, k’zie rid- en runders draven, with Charivarius’ continuation ‘k zie vo- en vlegels zich aan wa- en bitter laven, up to lust- en korensc-hoven.

——————

4. CLEAR BAMBOO RANGE

斤

樵 暗 青 檀 竹

人 入 翠 欒 嶺

不 商 漾 映

可 山 漣 空

知 路 漪 曲

Axe/pound Bamboo Range / sandalwood (tree) brilliant empty twist/curve / *green/shiny *blue-green agitated ripple (-) / *dark/secret enter Shang mountain road / woodman man not can know

Clear Bamboo Range Bamboo Hill

Tall and dense, they gleam by the empty riverbend; Tall bamboos reflected in the meandering river

Azure-green, billowing, flowing waves. So the rippling river drifts blue and green

Secretly enter the Shang Mountain Road: We are on the Shang Mountain track unobserved -

Woodcutters cannot be known (Polly) Something no woodman would understand (Mrs. Robinson)

A Hill of Graceful Bamboo Bamboo-Clarity Mountains

Sandalwoods cast shadows among empty trails. Tall bamboo blaze in meandering emptiness:

Dark blue ripples race on the river. kingfisher-greens rippling streamwater blue.

Secretly I enter the pathway to Mount Shang; On Autumn-Pitch Mountain paths, they flaunt

Not even the woodcutter knows I am here. (Woolmsley) darkness, woodcutters there beyond knowing. (Dinton)

Clear Bamboo Range

crown of top leaves, thick

forest creek, some deer

kingfisher zooms by, quick

woodmen don’t come here.

(Ferryman)

(kingfisher *blue is just a color - but the image of such a bird flying low over a *forest *creek,

bringing out the vastness of a forest space, seen from some elevation, forced itself on me)

Polly: “This refers to the famous hermits known as the “Four Whiteheads” who, when the first Qin emperor came to power in 221 BC., retired to Mt. Shang in Shaanxi province and refused to serve in this autocratic government. Records of the Historian, 55/2045” —— Mrs. Robinson: “Tsuru is surely *right in saying that this poem is an allusion to the Four *White Ones, four worthies who took refuge from the savagery of the Ch’in (Qin) regime on Mount Shang, one of the Chung-nan (Zhongnan) range - a woodman would not be sufficiently erudite to have similar thoughts” —— The Chang/Walmsley version gives perhaps the correct translation of the last line. The poet is simply so deep in the *forest that even woodmen are not familiar with the place, or don’t come in that part of it. *I like Robinson’s take on erudition, but only as allusion - he should not have made the text unequivocal. Besides, wouldn’t the spiritual growth of the Taoist/Buddhist seeker be what would make the woodcutter ignorant? —— Dinton seems to go a bit off the wazoo in this one … How far should the poet wander from the broad road?

——————

5. DEER PARK

鹿

復 返 但 空 柴

照 景 聞 山

青 入 人 不

照 深 語 見

上 林 響 人

Deer wood/enclosure / empty mountain not see *man / however hear *man voice echo/sound / contrast shadow* enter deep *forest / again shine *blue/green moss upon —— (景 ‘ing’, though I mostly find it under ‘ching’, = ‘shadow’, actually means a sort of chiaroscuro: a light topic against a dark background, or vice versa)

This poem is one of the most famous poems of the entire body of Chinese poetry. Elliott Weinberger published a booklet called Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, which can be found on line under jonvonkowallis.com (I have the actual booklet in box 17 of my stored books). In it, he gives 19 translations of this poem, some of which I am giving here (he was not familiar with prof. Idema’s 1991 Dutch translation). I can really recommend this little booklet, it has some very good insights. The probably unintentionally hilarious last entry is from there too.

Deer Enclosure Deer park

Empty mountain, no man is seen. Nobody in sight on the empty mountain

Only heard are echoes of men’s talk. but human voices are heard far off.

Reflected light enters the deep wood Low sun slips deep in the forest

And shines again on blue-green moss. (Polly) and lights the green hanging moss (the Barnstones)

Deer Fence Deer Enclosure

Empty hills, no one in sight, Empty mountain: no man

only the sound of someone talking; But voices of men are heard.

late sunlight enters the deep wood, Sun’s reflections reaches into the woods

shining over the green moss again. (Dr. Watson) And shines upon the green moss. (Yip en Yanneke)

The Deer Enclosure Deer Forest Hermitage

In pathless hills no man’s in sight, Through the deep wood, the slanting sunlight

But still I hear echoing sound. Casts motley patterns on the jade-green mosses

In gloomy forests peeps no light, No glimpse of man in this lonely mountain

But sunbeams slant on mossy ground. Yet faint voices drift on the air. (Woolmsley)

X.Y.Z. - (Why the switch of the two verse pairs? The flow from our world in the negative . to Spirit manifested in Creation in the positive is ruined…)

Deer Park Lu Park

Hills empty, no one to be seen This mountain has an air of emptiness. (“air”, really?!!!!)

We only hear voices echoed - Men’s voices are heard though no man can be seen.

With light coming back into the deep wood Sunbeams filter through dense, darksome woods

The top of the green moss is lit again. (Robinson) Glimmering on rocks whose moss shines rich and green. (Chaos)

Weinberger’s commentary - henceforth known as ‘Wein’s whine’: “Robinson’s translation, published by Penguin Books, is, unhappily, the most widely available edition of Wang in English. In this poem Robinson not only creates a narrator, he makes it a group, as though it were a family outing. With that one word, we, he effectively scuttles the mood of the poem. Reading the last word of the poem as top, he offers an image that makes little sense on the forest floor: one would have to be small indeed to think of moss vertically. For a jolt to the system, try reading this aloud.” (Eliot Weinberger)

(No title) Het Hertenkamp (No title)

Empty mountains: De lege berg: je ziet geen mensen, No se ve gente en este monte,

No one to be seen. Je hoort alleen de echo van hun stemmen. sólo se oyen, lejos, voces.

Yet - hear - Het kerend zonlicht door het diepe woud. Bosque profundo. Luz poniente:

human sounds and echoes. Beschijnt opnieuw het groene mos. alumbra el musgo y, verde, asciente

Returning sunlight (Idema ) (Octavio Paz)

enters the dark woods;

Again shining

on the green moss, above. (Snyder) -

“The reason for ‘moss, above’ is that the sun is entering (in its sunset sloping, hence ‘again’ - a final shaft) the woods, and illuminating some moss up the trees (not on “rocks”). This is how my teacher Ch’en Shih-hsiang) saw it, and my wife (Japanese) too, the first time she looked *at the poem.” - (Gary Snyder 1978) ——— To add my tuppence: I think Schneider or however his name has found the perfect way to render the concise universality of the Chinese imagery in the much more specific and specifying English language.

Deer Park Deer Forest?

No one seen. In empty mountains No one seen on the bare mountain

hints of drifting voice, no more. only echo voices heard;

Entering these deep woods, late sun- sunlight piercing the deep forest

light ablaze on green moss, rising (Dinton) green on the shining moss. (Bill Keith)

D(avid H)inton is :-(was) a very well known translator whom *I thought of as a klugscheißer (‘clog sizer’). Reviewing that possible prejudice, I like drifting voice , especially the singular, as well as ablaze. The enjambment is of course violating the original, but doesn’t it capture the last sunlight penetrating the darkening woods? —— Bill Keith (as *I know him) is a retired professor English literature in *Toronto. These translations were never published, he gave them to me in a portfolio (the only kind of portfolio I’ll ever have); I included them here because I like them at least as much as most published translations. Like the ones here following…

The form of the Deer (?) The Deer Park

So lone seem the hills; there is no one in sight there. An empty hill, and no one in sight

But whence is the echo of voices I hear? But I hear the echo of voices.

The ways through the sunset pierce slanting the forest The slanting sun et evening penetrates the deep woods

and in their reflection green mosses appear. (J.B. Fletcher) and shines reflected on the blue lichens. (Soame Jenyns 1944)

Wein’s whine: “(Fletcher’s) translation is typical of those written before the general recognition of Ezra Pound's Cathay, first published in 1915. Pound's small book, containing some of the most beautiful poems in the English language, was based on a notebook of literal Chinese translations, prepared by the orientalist Ernest Fenollosa and a Japanese informant. The "accuracy" of Pound's versions remains a sore point: pedants still snort at the errors, but Wai-lim Yip (here called Yip & Yanneke R.) has demonstrated that Pound, who at the time knew no Chinese, intuitively corrected mistakes in the Fenollosa manuscript. Regardless of its scholarly worth, Cathay marked, in T.S. Eliot's words, "the invention of Chinese poetry in our time." Rather than stuffing the Original into the corset of traditional verse forms, as Fletcher and many others had done, Pound created a new poetry in English drawn hom what was unique to the Chinese. (…) Pound's genius was the discovery of the living matter, the force, of the Chinese poem- what he called the "news that stays news" through the centuries. (…) —— Fletcher explains his curious (and equally Platonic) title with a note that chai means ‘the place where the deer sleeps, its 'form'.’ ”

Especially (this is me speaking) in made-in-china translations I still find rhyme sometimes (Fletcher uses a half rhyme). I find that catastrophic, because it completely destroys the directness and the flow of the Chinese. I normally find rhyme in translations problematic, because it forces to deviations from the actual meaning, resulting in my reading Mandy Perosi or Elisabeth Youngstown or Ronald Plump, or whomever, instead of Dante. The only rhyming translation of something I liked was a modern German one of the Nibelungen saga, as literal prose translations of those works, unlike Homer and Virgil, are excruciatingly lame. Again, my own rhyming versions of these poems are re-creations, which abandon the literal text necessarily at points.

Jenyns’ version Weinberger calls “dull, but fairly direct.” He also comments on ‘lichen’ instead of moss, adding “but in its plural form the word is particularly ugly”. Perhaps he is right. I am not from here. That’s probably why I love country music. It breathes the freedom of the (dying) American spirit, and I never had to live with the arrogant, dimwitted and extremely parochial mentality of those who blast it on the radio all the time. Or so I think. Perhaps the dislike of country in my circles itself comes from the arrogance and bigotry of the “civilized”.

5. Deer Pen

mountain, oak and beech

sunlight, late, shines through

moss glimmers in its reach

woods grow still, anew

(Ferryman)

Finally something hilarious, and I have even nothing to do with it! Someone called Peter Boodberg shows the absurdity of scholarship without inner poetry or rather human sense. It is too bad that it becomes good again. Isn’t there a society that advocates real bad poetry, wasn’t there something called the Bulwer-Shytton Society? - this highly entertaining effort with its the Monty-Python-like absurdity is highly entertaining. What sort of mind would think of something like this?!!!

“A still inadequate, yet philologically correct, rendition of the stanza, with due attention to grapho-syntactic overtones and enjambment”

The empty mountain; to see no man,

Barely earminded of men talking - countertones,

And antistrophic lights - and - shadows incomer deeper the deep - treed grove

Once more to glowlight the blue-green mosses- going up

(The empty mountain) (Peter Boodberg)

“Still inadequate shows that the author really thinks that his version can stand next to all the others. Oh, the difference between true genius and sheer delusion! And it is philologically far from correct! Ever seen of sunlight going up from the mosses? He completely seems to misunderstand the word 上 shang the Shang of Shang Hai).

——————

Magnolia Fence

木

夕 彩 飛 秋 蘭

嵐 翠 鳥 山 柴

無 時 逐 斂

處 分 前 餘

所 明 侶 照

Magnolia enclosure / autumn mountain connect remnant shine / fly bird chase in-front mate / brilliant *blue-green time separate clear / *evening *mist no place place/dwell

Magnolia Enclosure Magnolia Enclosure

Autumn mountains embrace the lingering light. Autumn mountains drink the sun’s last rays

Flying birds follow companions ahead. Floating birds follow their mates.

Brilliant blue-green - at times distinct and clear; At this hour colors leap into clarity.

Evening mists without a place to be. (Yu) No place for evening mists to dwell. (the Barnstones)

Floating birds??? On the water, or what? 飛 (fey) clearly meant flying. I just asked my beloved Marie-Thérèse for her associations on floating birds, and she mentioned, as I would, swans on the water. Gliding birds, perhaps would have been better. But the, why not just flying?

Magnolia Park Magnolia Hermitage

Autumn hills taking the last of the light The autumn hills hoard scarlet from the setting sun.

Birds flying, mate following mate Flying birds chase their mates,

Brilliant greens here and there distinct Now and then patches of blue sky break clear…

Evening mists have no resting place. (Mrs. Robinson) Tonight the evening mists find nowhere to gather. (Walmsley)

Magnolia Park David Hinton

Autumn mountains gathering last light, David Hinton, poet-interpreter

one bird follows another in flight away. Inspired, delivers a thundering line

Shifting kingfisher-greens flash radiant Then - O Affect! - kingfisher greens

scatters. Evening mists: nowhere they are. (Dinton) And cardinal red aware. Sense is not. (Ferry R.)

David Hinton’s translation of this poem is the one that give rise to my parody on him, which you find next to it. His translation here is somewhat inconsistent with most of his translations, which are always beautiful, and mostly quite sensible. True that. I have of course a theory about this: the above translation is from the real Dinton, while the majority of his work was actually written by his wife. Of course there isn’t a shred of evidence supporting this theory - actually just a hypothesis, a real theory, like evolution, is infinitely more sure - except that it is fashionable today to suspect an author’s wife to be the real author of someone’s oeuvre. We believe what we want to believe. I really like this theory because 1. it’s mine and 2. it sounds good. But hasn’t that become the main criterium for the media to operate on for a while now?

I found nothing about the last line. Evening mists no place dwell. To me it seems that the mists are moving, no place for them to settle - otherwise, why mentioning them? But perhaps Walmsley is right: on this night, no place for mists. Is this the clarity of spiritual awareness? In any case, in my re-creation I was so impressed by the many landscape pantings that the mists simply had to be there ….

Magnolia Fence

fall hills and hills, late light

birds flying, following mates

all’s blue and brilliant - slight

mists rise, at random rates

(Ferry Reno)

——————

7. DOGWOOD BANK

茱

置 山 復 結 萸

此 中 如 實 沜

茱 倘 花 紅

萸 留 更 且

杯 客 開 綠

Dogwood Bank / tie *fruit *red and *green / again if flower even-more open / mountain midst if stay guest / put this (Cornus off.) (-) cup - (Cornus officinalis = Japanese cornel dogwood)

Dogwood Bank Dogwood Bank

They bear fruit red and green, The fruit is forming red and yet green

And then, like flowers, blossom once again. And it is if flowers were opening again

In the mountains, if guests are to stay, If I detain a visitor in these hills

Prepare this dogwood cup. (Polly) I may offer him this dogwood cup (Robinson)

Rivers of Dogwood Dogwood bank Rivers of Dogwood

Green dogwood berries ripen to crimson Fruit ripening in reds and greens, Plagiarism!!! For some reason,

Though blossoms still star the branches it’s like they’re in bloom again! the Chaos copy Walmsley’s

Come friends! How can you bear not to stay in these mountains To keep guests in these mountains translation of this poem

And savour that rich wine with me! (Woolmsley) just offer them this dogwood cup. (Hinton) on their CD!

Walmsley loses the serene intimacy of a conversation with ‘one true friend’, I’m just sayin’ … Wang’s quietism does not lend itself to partying …

7. Dogwood Park

fruits, red on green, the ground

scents up - and views, sounds blend …

ravines … I keep around

a dogwood cup - for_a friend

(Ferry Reno)

——————

8. SOPHORA PATH

宮

畏 應 幽 仄 槐

有 門 陰 徑 陌

山 但 多 陰

僧 迎 綠 宮

來 掃 苔 槐

Sophora path / oblique path shade palace Sophora (now Styphonolobium) Japonica / secluded shadow much *green moss / responsible door but welcome sweep / *fear/awe have mountain monk (*Buddhist) come

Sophora Path Ashtree Path

The bypath is shaded by sophoras; The approach is by a side path, ashtree shrouded

In secluded shadows, green moss is thick. Secluded, shadowy; moss decks the mountain wall.

But the gatekeeper sweeps it in welcome Boy, sweep the path to give our guest a welcome;

In case the mountain monk should come. (Polly) Perhaps today the mountain monk will call? (Chaos)

(The Chaos seem to have borrowed again from some or other British translator. I included it because I liked the mossy mountain wall image. However, “Boy” and its whole passage trivializes the narrative)

A Path through Imperial (sic!) Locust Trees Scholartree Walk

The narrow path hides beneath imperial locust trees; On the side path shaded by scholar trees,

Thick green mosses carpet the shaded earth. Green moss fills recluse shadow. We still

While sweeping the courtyard, I keep watching the gate keep it swept, our welcome at the gate,

lest my friend, the mountain monk, should visit me. (Walmsley) knowing a mountain monk may stop by. (Hinton)

“My friend” ????? And where the f*$%!cking sh$%#!t did Walmsley get that G$%#dd@#$ned“*Imperial” from?!

8. Scholar tree path

scholar trees shade the trail

mint spots of wet moss, drunk

kept clean, though, head to tail

in case he comes, the monk

(Ferry Reno)

——————

9. LAKESIDE PAVILLION

臨

四 當 悠 輕 湖

面 軒 悠 舸 亭

芙 對 湖 迎

容 樽 上 上

開 酒 來 客

above/look-down-on lake kiosk / light barge welcome upon guest / far far lake upon come / facing pavillion toward carafe wine / 4 face hibiscus (-) open

Lakeside Pavillon Lakeside Pavillon

A light bark greets the honored guest, A light boat greets the honored guests,

Far & distant, coming across the lake. Far, far, coming in over the lake.

On the porch, each with goblets of wine On a balcony we face bowls of wine

On all four sides lotuses bloom. (Polly) and lotus flowers bloom everywhere. (The Barnstones)

Arf! Arf! Arf! A Yorkshire Terrier? A - I wouldn’t call it ‘dog’ - barking on a tree barked bark. Is it just me taking the wrong - because it’s the far more common - meaning of the word? In this context 'the more boring ‘boat’ seems better. Or may I suggest a different spelling?

In an Arbour beside the Lake Lake Pavillion

My light skiff, garnished to welcome esteemed guests, Light boat to meet the honoured guest

Leisurely floats along the lake. Far far advancing over the lake

On the shaded balcony we sit with our wine-cups We gain the balcony and sit with our wine

Mid lotus blossoms blooming in four directions (Woolmsley) and lotuses are opening all about. (Robinson)

Again, the first person possessive loses the mystery of the image of one boat on a large, serene lake, slowly approaching. Even though Chang/Walmsley (that would be Zhang/Woolmsley today in ‘American’ and pinyin’) published their translations in 1958, I think I can detect a turn-of-the-century European approach. No matter how beautiful, I would probably have preferred if Ravel had written a Chançon de la Terre on poems of Li Bai instead of Mahler’s Lied von der Erde. “My skiff” makes things familiar and predictable. It would make the “Schiffer” the narrator. Other than that, Ohio State fans would like the British spelling of *Arbor, though they might one-up this to Are-bore. I wonder how many Buckeyes thought of this pun before I just did.

Two of these translations bring the twin-word 悠悠 yoyo (don’t know if this is the same word as Yo Yo Ma’s name, though he is far far removed from me in many many different ways ways) over in English. Twin words, I understand, bring vagueness and unbestümmtheit to the T’ang idiom, somewhat like the bumper sticker ESCHEW OBFUSCATION. This is another way in which Woolmsley fails: there is nothing distant and indistinct about the skiff, which mood in the Chinese is so overwhelming that even I observe it.

(Yoyo Ma is spelled 馬友友 in Chinese, - ‘horse’ ‘friend’ ‘friend’ - pronounced not unlike “Ma yoyo!”. I can imagine his father finding his favorite toy in bed after Yoyo’s conception and thus giving the baby his name by his happy exclamation. I strongly believe, from my impressions and experience, that Yoyo Ma must be the nicest man who has ever been born in Paris).

9. Lakeside Pavilion

cross the lake - smooth shine -

approaching barque: my guest -

on the porch, the wine

midst lotus blossoms, blessed …

(Ferryman)

——————

10. Southern Hillock

南

遙 隔 北 輕 垞

遙 浦 垞 舟

不 望 淼 南

相 人 難 垞

識 家 即 去

South hillock / light boat south hill go / north hillock flood difficult pass-through / across bank look for *man home / far far not each-other know

Southern Hillock South Hill

A light skiff leaves for Southern Hillock. A small boat sails to South Hill

To Northern Hillock, wide waters are hard to cross; North Hill is hard to reach - the river is wide

On the other shore I gaze at people’s houses: On the far shore I see families moving

Far and distant, we do not know each other. (Polly) Too distant to be recognized (Walmsley)

Hinton’s, I wrote in 2015, is by far my favorite last line. The most universally meaningful FR. —— Woolmsley: ‘why would a wide river be an impediment to reach a shore? And if the river is truly wide, one would not be able to see any human beings the other side. I’m sure the good man was used to British rivers; which don’t even impress to the puny European standards, where the largest river, the Danube, may well compare to the Ohio river, but disappears into obscurity against the real giants of the world, Nile (which however disappointed me in Cairo), Mississippi/Missouri, 長江, Yangtze, Wolga (Волга), On, and the largest of all, the Amazon.br. Everything hinges on the word 淼, which my enormous Gudai Dictionary (古代漢語詞典) explains as “big surface of water, infinite” — Polly’s “Wide waters” and Woolmsley’s “the river is wide” however does not seem to adequately cover the word, the character of which, 淼 constitutes of the (full) character for ‘water’ 水 written three times over. I like the Barnie Barnstones’ ‘harsh waters’. Dinton probably wins though, see below, with his ‘vast’ and ‘never’. I begin to see him more and more as a literary Brett Favre, who threw many interceptions, just by his sheer daredevil, swashbuckling guts; but who also threw many unforgettable, legend - wait for it - dairy touchdown passes. I guess he is still around, perhaps he might read this and smile, he doesn’t seem to be too uptight. In any case, a comparison to Brett Favre is one of the greatest compliments a male human can get from me. It should be clear that the parody I place here, as opposed to the one above under 6. Magnolia Enclosure, is not on his translation, but on an association I have with the title.

South Hill South Hill

A light boat is heading for South Hill. My light boat can get to South Hill.

North Hill faint beyond harsh waters. North Hill is hard, the water is wide

Houses and people across the lake, On the other shore we can make out houses

I see them far, far. We are strangers. (the Barnstones) Far, far, people we can’t recognize (Mrs. Robinson)

South Point West Point

I leave South Point, boat light, water the West Point shore, an old pine tree on

so vast you never reach North Point. some salty sand, incoming wave -

Far shores: I see villagers there beyond some day I will return - to pee on

knowing in this distance, distance (David David Hinton Hinton) that motherfucker sergeant’s grave (couldn’t resist, Ferry)

Southern Hillock

rough tide, the waters wide

the skiff’s too light to row

far homes on the_other side

souls no one gets to know (Ferry Reno)

——————

HERE ENDS THE FIRST HALF OF THIS ANTHOLOLOGY

——————

List of translators:

*The Barnstones = Not Fred and Wilma or Barney and Betty, but Tony and Willis Barnstone,

Chaos = Gao Jian-yi, on George Gao’s CD Music Link over Centuries: Wang Wei, *Toronto 1999

Dinton = David Hinton, The Selected Poems by Wang Wei, 2006

Mrs. Robinson = (Mr.?) G.W. Robinson, Wang Wei, Poems, Penguin Classics, 1973

Woolmsley = *Chang Yin-nan and Lewis C. Walmsley, Poems by Wang Wei, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1958

Dr. Watson = Burton *Watson, The Columbia Book of Chinese *Poetry, Columbia U. Pr., *New York

Prof. Idema = W.L. Idema, Spiegel van de klassieke Chinese poëzie, Meultenhof, Amsterdam, 1991

X.Y.Z. = *Xǚ Yüān Zhōng, 300 Tang poems, Higher Education press, China, 1999

Xu Haixin, Laughing Lost in the Mountains: Poems of Wang Wei, University Pr. of *New England

Young = David Young, Five T’ang Poems, *Oberlin College Pr., 1990

Yip & Yanneke = Wai-lim *Yip, Chinese *Poetry, An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres, Dule U. Pr., 1997

Polly = Pauline Yu, The *Poetry of Wang Wei, Indiana U. Pr., Bloomington IN, 1980

officially unpublished or unofficially published:

Bill Keith = William ? Keith, *Toronto

Ferry Reno, Ferryman, Fr. = 渡復興 (Du Fuxing), AKA René Antoine Duchiffre, AKA me …

(A list of authors and a glossary will be provided at the end of the second half)

——————

Carousel

1. 洞天山堂Dong Tian Mountain Hall by 董源 Dong Yuan, d.962 —— Landscape with Deer Hunt, 1593, by Pieter Bruegel ——